After WWII, Charles de Gaulle boosted the French economy and helped road haulers, farmers and artisans who depended on diesel by reducing the taxation on this fuel for the first time.

Later, in 1980, Toyota and its revolutionary production model flooded the French market with economical and reliable cars. At the same time, France replaced all its diesel-based power plants with nuclear ones to ensure energetic independence. In addition, the French government offered new diesel incentives to increase the competitive advantage of local manufacturers, specialized in diesel motors, and get rid of the million litres of now useless diesel from the power plants.

Today, 61% of cars in France run on diesel (INSEE, 2018), one of the highest proportions in Europe. This situation generates significant environmental and public health issues. Indeed, diesel engines emit more fine particulate matter (PM) than their gas counterparts, increasing air pollution and provoking lung cancer.

According to (European Commission, 2015) and (Anenberg, et al., 2017), around 10,000 people die annually in France because of diesel. Furthermore, air pollution costs 100 billion euros to the country each year (Aichi, 2015). Also, the European Commission is currently investigating eleven French cities for exceeding authorized pollution thresholds.

Faced with this alarming situation, the government attempted to reduce incentives, aligning diesel and gas taxations. This measure was the tipping point for the French people, known for their spirit of revolt, who did not fail to react, giving birth to the movement of the yellow jackets. It has been seven months since this revolt paralyses one of the most powerful countries in the world.

This document aims to analyse the role played by incentives in this matter, identify what could have been done differently and provide potential solutions to the current situation.

Situation Analysis

After the war, de Gaulle’s incentive smoothed the business cycle when the economy was at its weakest (as theorized by Keynes). The incentive was correctly calibrated as it benefited businesses and did not significantly change private consumers’ behaviour. After the 1973 oil shock, diesel cars became more appealing to individuals because of their lower fuel consumption. French manufacturers took this opportunity to invest in this technology.

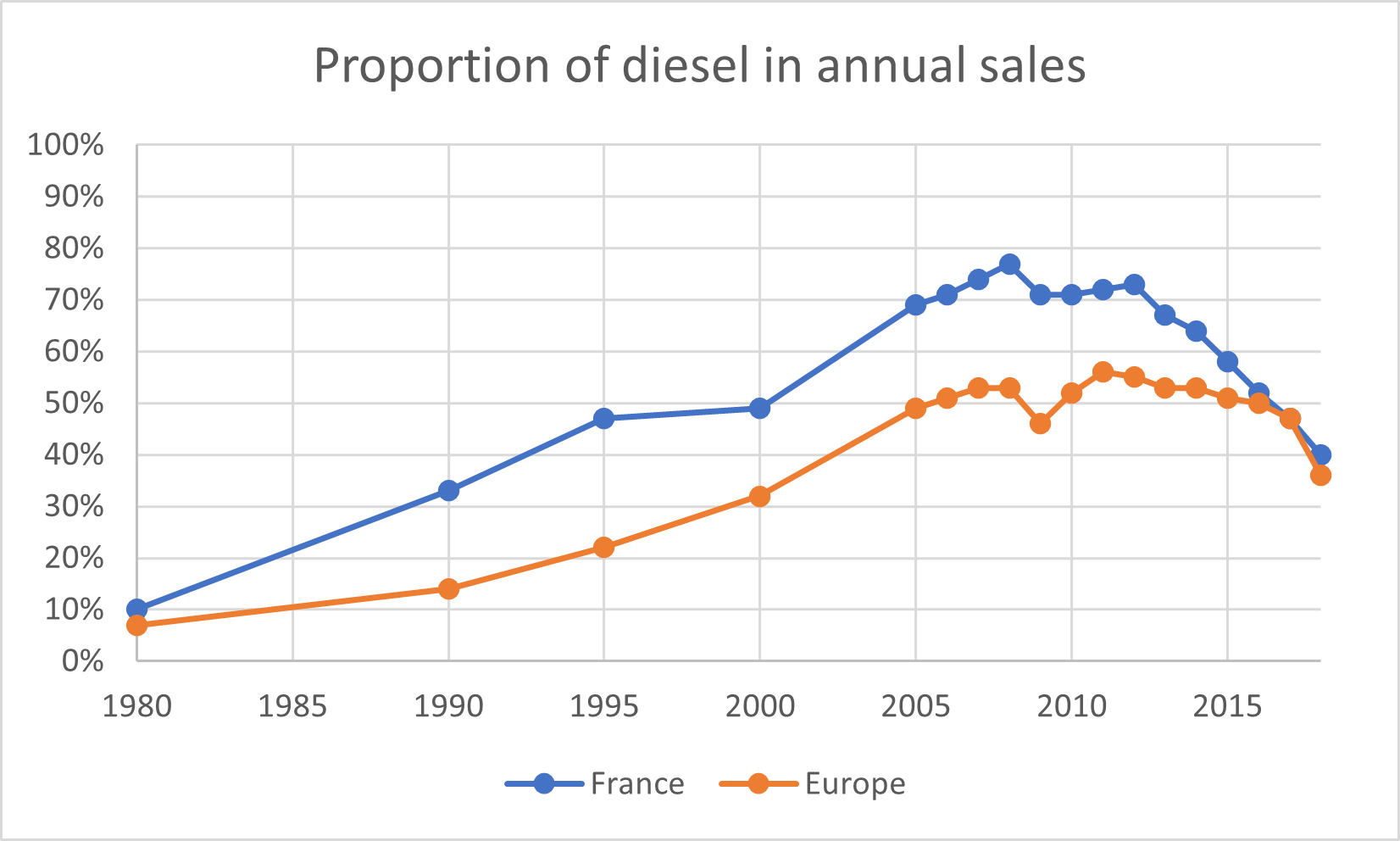

Figure 1. – Source: (L'Argus, 2015)

In 1980, Toyota was killing the competition thanks to its exemplary production model highly inspired by Deming. The government reduced the taxation on diesel fuel again and offered VAT deduction for businesses to increase French manufacturers’ competitive advantage (i.e. their knowledge of diesel engines). As a result, the proportion of diesel vehicles tripled in France between 1980 and 1990, while it only doubled in the rest of Europe (see Figure 1). French people made what seemed the most rational decision from a financial point of view. However, the opportunity cost – their health – was huge and overlooked. This sub-optimal decision was undoubtedly the result of an information asymmetry: the general population was not fully aware of the dangers of diesel.

During the 2000s, manufacturers marketed diesel as ‘clean energy’ since it generates less greenhouse gas (GHG) than petrol (BP, 2000). Marketing campaigns in favour of diesel and technological advances to create more powerful diesel engines led to an explosion of sales to a level that remained stable until 2012. After, increased awareness of PM resulted in new regulations (e.g. Euro 6) and lower tax incentives for individual consumers. Thus, the cost of owning diesel cars rose, decreasing their value compared to petrol-based models. In 2015, the ‘diesel gate’ was the final nail in the coffin for diesel vehicles.

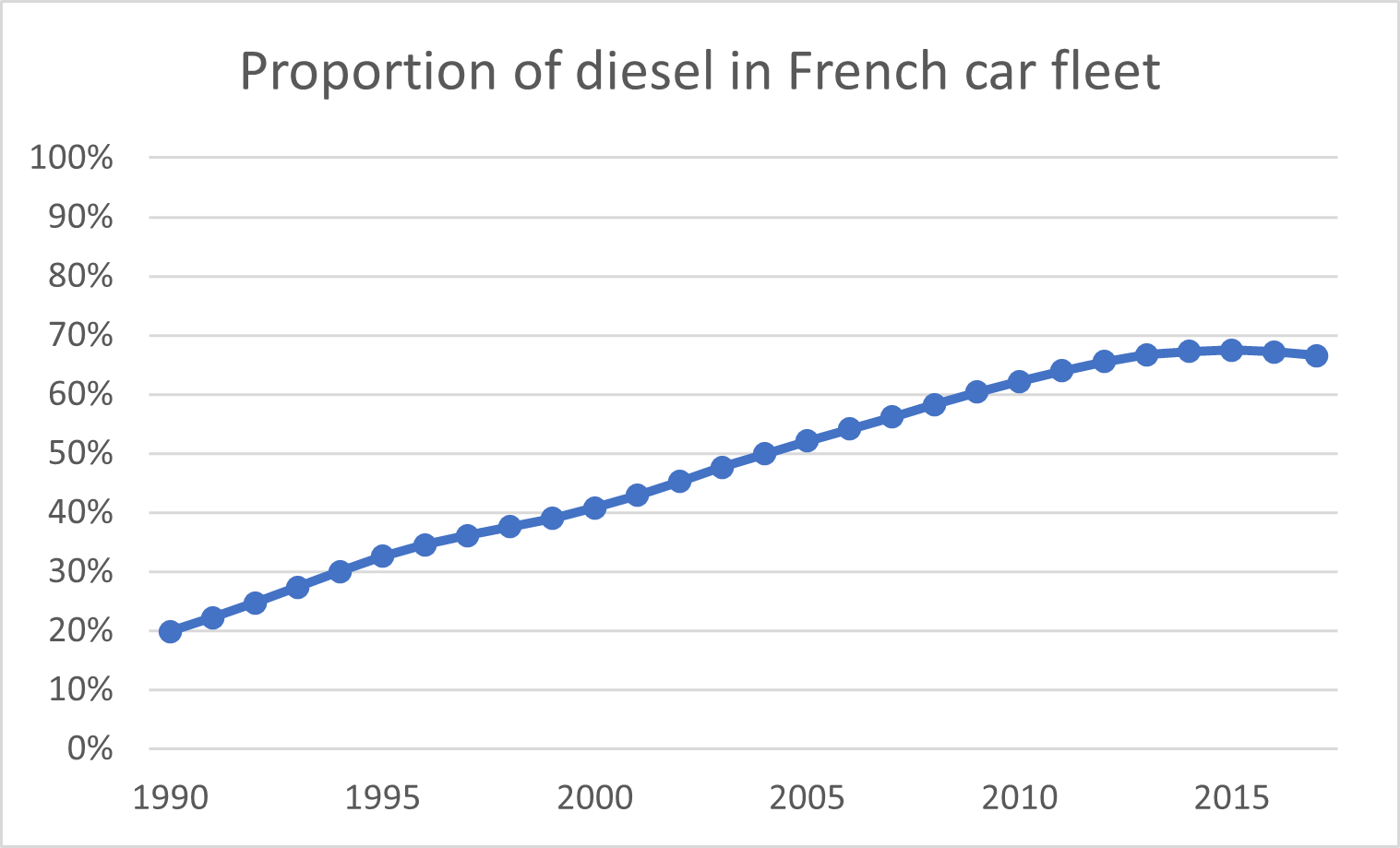

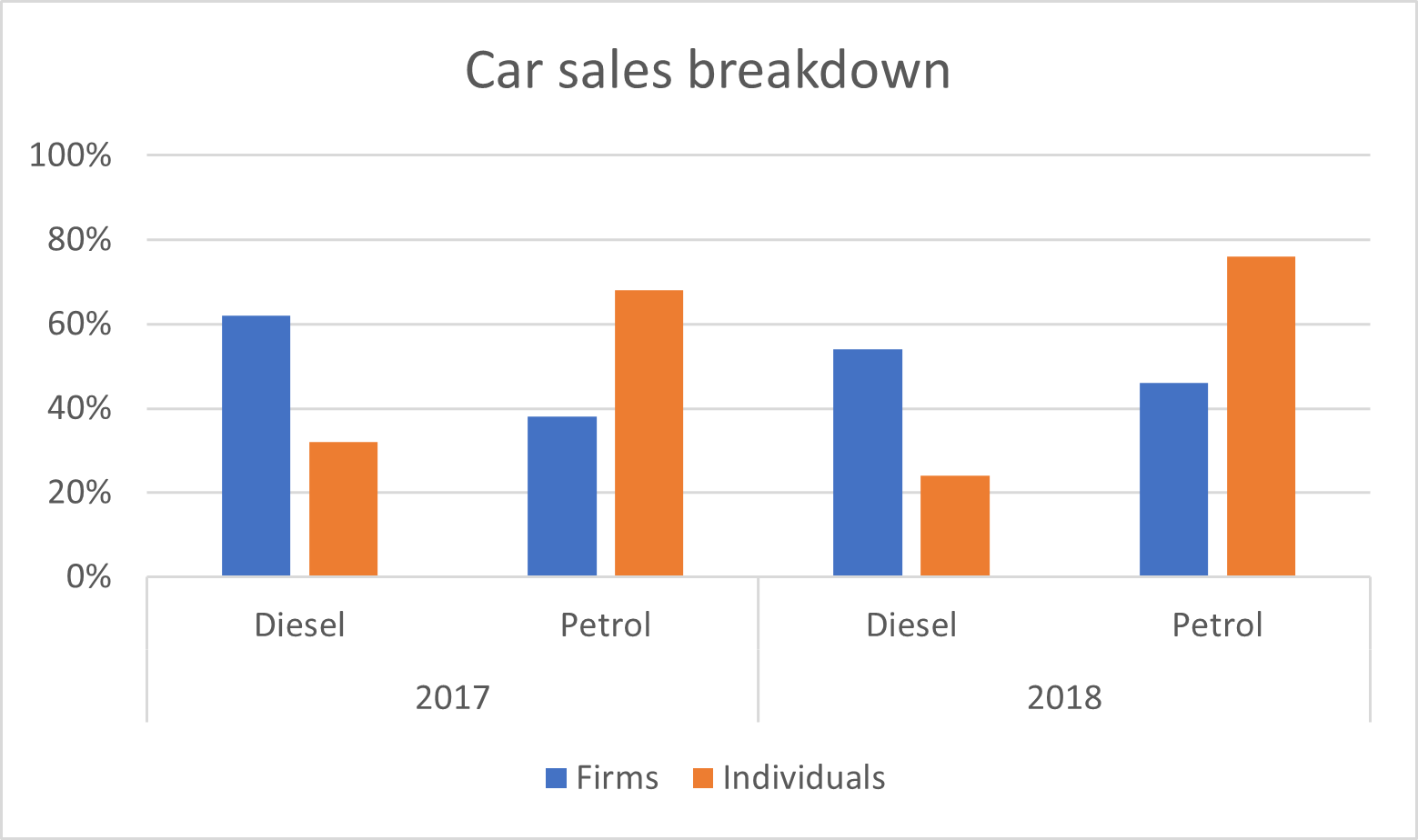

The last two decades left the country with many diesel cars in circulation (see Figure 2). People, therefore, depend on this fuel, and the government is left with little room to ease the transition to less harmful vehicles. On top of that, lobbies and diesel-dependent corporations push back every attempt to narrow the incentives’ scope, threatening to suppress jobs and freeze the country with strikes. Consequently, incentives for companies are still in place and remain extremely attractive (see Figure 3).

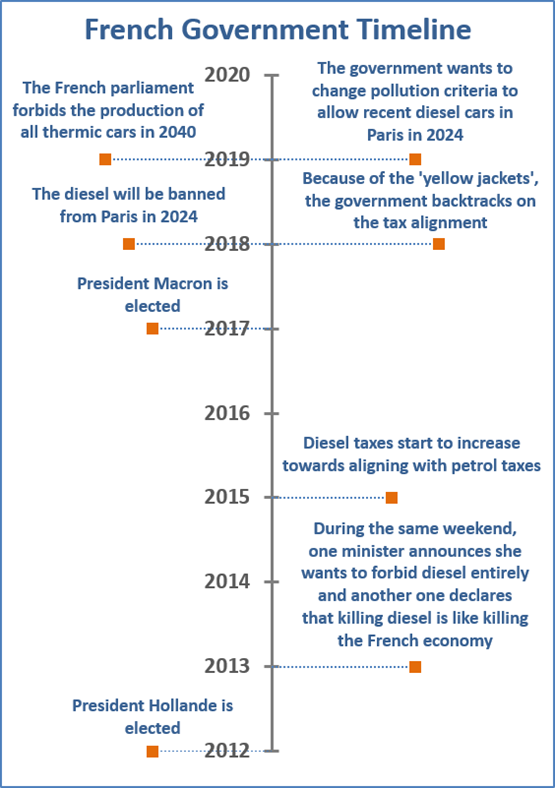

In this context, the government struggles to provide a clear vision in this matter (see Appendix 1: French Government Timeline). And unfortunately, all these uncertainties and mixed signals around diesel and thermic cars do not create an appropriate environment for consumers to make relevant decisions, especially such as buying a new car.

Considering the information above, one can wonder whether the French government made the right decision in the eighties. It arguably saved the French car industry, but at what cost? Indeed, the government was already aware of the adverse effects of diesel. They even had a report explaining the risks of diesel-powered engines and recommending stopping their production (Roussel, 1983).

Moreover, Toyota was not winning the market because of unfair advantages (like cheap labour). Instead, the company’s understanding of variation and continuous improvement mindset allowed them to reduce waste and consistently produce high-quality cars at lower costs (The Deming Institute, 2007). The government tried to regulate the economy and disturbed the signals consumers and firms were sending to each other (what Smith called the ‘invisible hand’). As Hayek predicted, this interventionism did not prove efficient. Furthermore, the primary goal of the government was to apply a form of protectionism. This kind of policy decreases the variety of products available for consumers and prevents companies from reaching their full potential in the absence of competitive pressure.

If the government had let the competition settle, French manufacturers would have improved their quality and performance or closed doors. Either way, consumers would have gotten better and less expensive cars. Regarding employment, Toyota would probably have created new jobs in France, counterbalancing the ones lost (as they did in 2001 when they created their factory in Valenciennes).

Figure 2. – Source: (INSEE, 2018)

Figure 3. – Source: (Auto BFM, 2018)

Assessment of Potential Solutions

As discussed above, the current situation is complex. Most government actions to address the issue have proved ineffective or, worse, led to adverse economic outcomes (e.g. the movement of the yellow jackets). This section aims to assess some existing initiatives and provide other potential solutions for the future. Negative incentives have been discarded as they would only widen inequalities by giving wealthy people the ‘right’ to pollute and pauperising the population, already on edge.

Expanding incentives to petrol

Since raising the diesel taxes to the level of petrol taxes is not a viable option, an alternative could be to expand all diesel-related incentives to petrol. The French government partially adopted this solution and will implement it for the businesses’ VAT deduction by 2022.

This alternative would remove diesel-specific incentives while raising petrol car owners’ purchasing power. As a result, the market will adjust, decreasing the proportion of diesel cars. Afterwards, the government could remove both incentives gradually in a fair manner.

On the other hand, it could also encourage people with tight petrol-related budget constraints to consume more. Indeed, the ‘income effect’ states that, for a constant income, a price fall loosens budget constraints. With the oil growing scarcity and global warming, this kind of incentive is not desirable in the long term but could be a relevant short-term trade-off.

Providing subsidies to change old vehicles

Providing subsidies to replace old diesel vehicles with new, cleaner, non-diesel ones is another potential solution. These subsidies already exist in France, but they are far from enough for low-income people, who tend to have old polluting cars. Besides, since the granted amount depends on the CO2 emissions of the new vehicle, it is a perverse incentive: many people use it to buy diesel cars.

An alternative is to increase further the subsidy amount for people who need it and reduce it for higher-income individuals. Also, all pollutant particles (e.g. PM) should be considered. Given the cost of air pollution mentioned before, a well-calibrated mechanism could be economically viable and beneficial for the country’s public health.

Encouraging electric cars

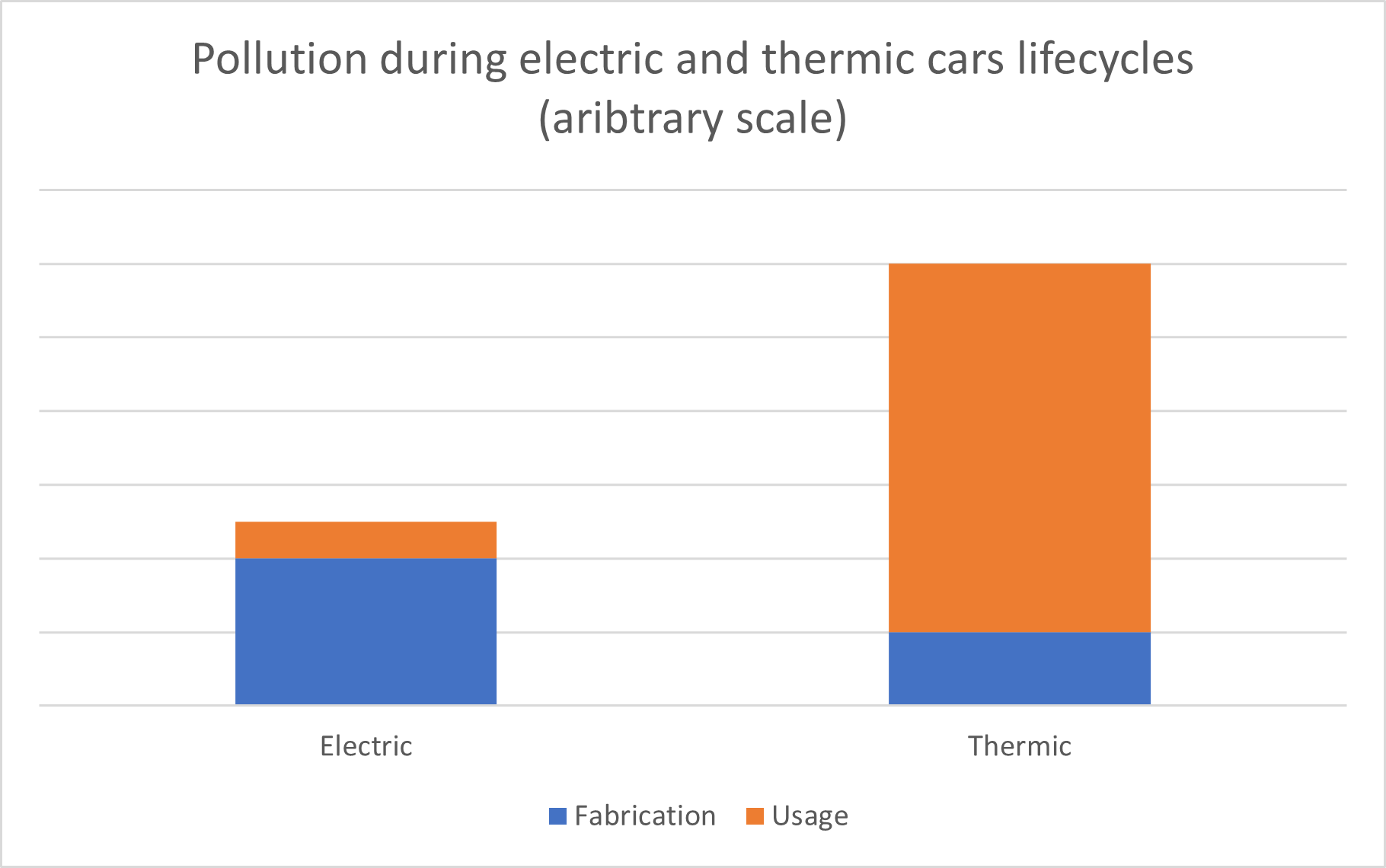

Electric cars are not as clean as they seem: their fabrication is twice as polluting as thermic cars’ one. The battery is the primary source of pollution because it needs rare earths, which require a massive amount of water and chemicals for their extraction. The pollution is then moved to producing countries like China or Brazil.

However, they emit two to three times less GHG and PM than thermic cars during their entire lifecycle (see Figure 4). Moreover, technological progress will decrease the reliance on rare earths for batteries and improve their recycling process (SAFT, 2018).

Figure 4. – Source: (EEA, 2018)

France’s electricity production, mainly nuclear (72%) and hydraulic (12%), generates a meagre amount of GHG and PM. Therefore, the country is a perfect candidate to leverage electric cars’ advantages for the environment. Also, France provides subsidies that make electric vehicles almost cheaper than thermic ones.

Soon, more competitive prices and a higher utility (e.g. greater autonomy and lower charging time) will increase the value of electric cars for consumers. Therefore, this future demand, social desirability and improved technology will shift the supply curve and reduce the part of thermic cars in manufacturers’ sales mix.

Reducing the need for cars

So far, governments and manufacturers have addressed the symptoms instead of the root cause of the problem. It is like prescribing aspirin to ease headaches provoked by meningitis, leading to kidney diseases in the long term. So why not change the entire paradigm? The idea is to withdraw cars from city centres to enhance air quality and general health. Indeed, one of the primary causes of air pollution is traffic congestion (Hermes, 2012).

Born during the 1980s in California, ‘walkable communities’ are the new trend in urban planning. They are self-contained neighbourhoods where one can live, work and spend leisure time within walking distance. Additionally, a mass transportation system connects them.

Extensive studies have proved these communities provide citizens with social, health and safety benefits (Talen & Koschinsky, 2014). They also have direct positive economic outcomes since they stimulate the local economy by creating jobs and encouraging people to spend more (Bent & Singa, 2008). Otherwise, once built, these neighbourhoods cost next to nothing to the cities as opposed to cars or buses (e.g. police, ambulances and operational costs). The millennials, who are 62% of the population, prefer living somewhere they do not need a car (Mundahl, 2018), and will shift the demand curve for this kind of project. Several cities, including Taiwan, Paris, Mexico City and Cairo, already have plans for walkable cities (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Paris Smart City Project

Conclusion

Economic interventionism can profoundly affect a country’s course. And not only on an economic level. Therefore, governments should adopt a systemic approach to assess incentives’ relevance and prevent these from backfiring. The history between France and diesel is fascinating in this regard, as it perfectly illustrates how seemingly similar incentives can lead to radically different outcomes.

In the post-war context, the lower taxation on diesel participated in the revival of the French economy. Back then, it was relevant for the government to absorb investment risks because infrastructures were in ruins, and the future was uncertain (the country had suffered two wars in 30 years).

In the 1980s, the country’s economy was also in jeopardy, but the context was incomparable, and the French government fought foreign competition with protectionism. While it would have made sense in a case of unfair competition (e.g. social, environmental or fiscal dumping), it resulted in lost efficiency, health issues and other adverse outcomes in this regular market economy situation.

Today, the government must intervene because the country is experiencing market failure caused by negative production and consumption externalities: prices for producing and consuming polluting energy do not consider environmental and health costs. Therefore, future solutions should consider these costs.

This analysis also showed that existing economic theories (e.g. Keynes, Friedman or Hayek views) could be valid depending on the context. Economic agents should not narrow their perspective to only one; there is no silver bullet.

Appendices

Appendix 1: French Government Timeline

Appendix 1: French government timeline

Sources

- Aichi, L. (2015). Pollution de l’air : le coût de l’inaction. Sénat, Paris.

- Anenberg, S., Miller, J., Minjares, R., Du, L., Henze, D., Lacey, F., . . . Heyes, C. (2017, May 25). Impacts and mitigation of excess diesel NOx emissions in 11 major vehicle markets. Nature(545), 467-471.

- Auto BFM. (2018, October 20). Qui achète encore des voitures diesel en France? Retrieved from BFM TV: https://auto.bfmtv.com/actualite/qui-achete-encore-des-voitures-diesel-en-france-1548163.html

- Bent, E. M., & Singa, K. (2008). Modal Choices and Spending Patterns of Travelers to Downtown San Francisco: Impacts of Congestion Pricing on Retail Trade. San Francisco.

- BP. (2000). Diesel ecology : Voiture disparue. Retrieved from INA: http://player.ina.fr/player/embed/PUB2346204085/1/1b0bd203fbcd702f9bc9b10ac3d0fc21/450/300/0/148db8

- EEA. (2018). Electric vehicles from life cycle and circular economy perspective. European Environment Agency.

- European Commission. (2015). Cleaner air for all. Retrieved from European Commission: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/air/cleaner_air/

- Hermes, J. (2012, January 5). How Traffic Jams Affect Air Quality. Retrieved from Environmental Leader: https://www.environmentalleader.com/2012/01/how-traffic-jams-affect-air-quality/

- INSEE. (2018, October 24). Véhicules en service en 2017. Retrieved from INSEE: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2045167

- L’Argus. (2015, February 15). Infographies : état des lieux du marché du diesel en France. Retrieved from L’Argus.fr: https://www.largus.fr/actualite-automobile/infographies-etat-des-lieux-du-marche-du-diesel-en-france-5955384.html

- Mundahl, E. (2018, February 7). Walkable cities are where people want to live, and spend. Retrieved from South Florida Sun Sentinel: https://www.sun-sentinel.com/opinion/fl-op-walkable-cities-popularity-20180207-story.html

- Roussel, A. (1983). Impact médical des pollutions d’origine automobile. French Ministry of Health, French Ministry for the Environment, Paris.

- SAFT. (2018, June 29). Trois technologies de batterie qui pourraient revolutionner notre futur. Retrieved from SAFT Batteries: https://www.saftbatteries.com/fr/media-resources/our-stories/trois-technologies-de-batterie-qui-pourraient-revolutionner-notre-futur

- Talen, E., & Koschinsky, J. (2014). Compact, Walkable, Diverse Neighborhoods:Assessing Effects on Residents. Housing Policy Debate, 24(4), 717-750.

- The Deming Institute. (2007). W. Edwards Deming: Prophet Unheard. Retrieved from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GHvnIm9UEoQ